A NARRATIVE ANALYSIS OF SUCCESSES AND FAILURES IN MANAGING THE PANDEMIC

Ivana Milojevic and Sohail Inayatullah

THE NARRATIVE CONTEXT

During the global financial crisis over a decade ago, the Financial Times (Yergin: 2009) reported that at its heart this was a narrative crisis. How one creates national policy and strategy depends on the story one uses. Depending on the narrative used – i.e., a mortgage crisis, a banking crisis, a geo-political crisis of the shift to the Pacific, a financial crisis, or even a crisis of capitalism – different strategies were created (Inayatullah, 2010). Some narrative are shallow and short term oriented; some destructive, and others constructing, leading to foundational changes for the better. Ultimately, in this example, solutions to deal with the deeper crisis (of capitalism) were eschewed, and Wall Street was saved at the expense of Main Street. Through massive spending, all returned to normalcy. The window of a possibility of structural change did not materialize.

We are in a similar turbulent situation today. As during the French Revolution, time is plastic: we have entered uncharted waters. What are the best global and national policies for dealing with COVID-19? As the virus continues to mutate and becomes even deadlier, will the vaccination strategy succeed? How severe or how long should lockdowns and quarantines be especially in poorer regions, as for example, South Asia? It may be that once the crisis nears its end, many will be tempted to go back to the world we knew i.e., one where nature is still seen as an externality, and profit is the core focus of all activities. However, as with the earlier financial crisis, this is also the opportunity to create a different world, to create structural changes in the global health system, in food safety, in climate change adaptation, to begin with. As biosecurity expert Peter Black argues, “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It can become a portal, a gateway between one world and the next” (Personal email, 6 April 2020).

What we do from here on – in response to COVID-19 pandemic and other challenges we currently globally face – will be decided by the narrative we use. It will also be decided by answering the following question: How much do we wish to change? As seen from many debates in relation to COVID-19, some people wish to “go back to normal”, yet others are still in various forms of denial in relation to the new reality. Parallel to this, various groups are promoting solutions focused on “changing the world radically”. Here, we have seen the polarisation between those wishing for more government control, even repression, and those wishing to use this crisis to create a more inclusive, economically democratic, and ecologically wise – a world with the characteristics of PROUT.

PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE

While there are many lessons from COVID-19 – a robust public health system and trust between citizens and government – the most important one appears to be being adequately prepared for the future. At a basic level, this means not just having the ability to read emerging issues and weak signals but also being able to rapidly respond to these signals. More, advanced futures-preparedness means that foresight is institutionalized into one or multiple branches of government. Ultimately, of course, futures-preparedness means a citizenry that is futures literate (Miller, 2018). This needs to be done at global, regional, and national levels as viruses do not respect borders. Returning to narrative as strategy, what metaphors and stories can help us move from being unprepared to being more prepared for the future, alternative futures?

We categorize approaches into meta-narratives: those that hinder and those that assist. Three that hinder are: blame, surprise/denial, and exceptionalism. Those that assist are global solidarity, planning, and social inclusion.

FROM BLAME TO GLOBAL SOLIDARITY

The first unhelpful position is based on electoral politics with the goal of gaining political capital by blaming others. The narrative used, by, for example, the former President of the US, Donald Trump has been, “the China virus” or “kung flu.” Blame can lead to a situation of a “battlefield” where the troops are rallied to fight the virus. The nation is seen as an organism, fighting the foreign virus. In addition, after blame, the worldviews of “herd immunity” and “natural selection” were used. This approach reduced preparedness and has resulted in nearly 600,000 deaths from COVID-19 in the USA by the end of May 2021. We have seen a similar situation in India where the virus has been linked to communal politics.

In contract to these narratives, there have been alternatives such as: “same story, different boats”, “global solidarity”, “viruses know no country”, and “all lives matter.” It is this second set of narratives, we argue, that is needed to be more adequately prepared for the future.

FROM SURPRISE AND DENIAL TO PLANNING

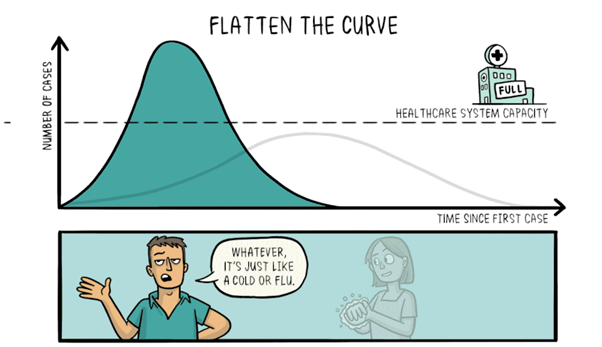

The second not so helpful frame or meta-narrative has been one of surprise. In this frame, the narrative has been, “who would have thought,” “sit back and wait for the avalanche”, and “never before” or a fatalistic “act of God”. Linked to this approach is denial as in the narrative of it is “just the flu” or traditional unproven treatments (cow urine, for example) are all that is needed. These narratives ensure a lack of preparedness and lack of decisive action as well as a rejection of scientific evidence.

In India, large gatherings were permitted to go ahead even when the clear scientific evidence suggested that they must not. And now, leaders pretend they are surprised. This denial of science has led to over 300,000 recorded deaths, though most scientists argue that it is dramatically higher.

In contrast are the narratives of “time is running out, use it wisely,” “pandemics are as certain as death and taxes”, and “man vs microbe” – a part of our evolutionary history and thus not a surprise. Challenging surprise/denial are also narratives such as “a new disease, a new approach” and “responding to signals amidst the noise”. Thus, in Australia, long-term thinking and modelling played an important role. For example, in March 2020, the Australian federal government was preparing for 50,000 deaths in a best-case scenario and 150,000 deaths in the worst-case scenario (Davey, 2020). Largely due to various measures taken, as of 14 December 2020, Australia had recorded 908 total deaths from COVID-19, and 28,031 of total cases (Government of Australia, 2020).

FROM EXCEPTIONALISM TO SOCIAL INCLUSION

The third frame or meta-narrative that hindered adequate preparedness and response has been exceptionalism, i.e., everyone else but me or my tribe or group. The most vulnerable (who are not ‘us’) are to be sacrificed via “only those with pre-existing conditions” (sick and elderly) narrative. The language used has been “not me, not us,” or “out of sight, out of mind.” Singapore, for example, had been a success story but it was remiss on COVID-19 strategies for poorer and neglected migrant workers. Their harsh working conditions – cramped, lack of access to medical care, lack of information on COVID-19 measures – led to an outbreak which then spread. This was also true for Sweden. The nation eschewed strict quarantine for trusting its citizens, but its policies did not create adequate safeguards for those in elderly homes and migrant communities, and thus the nation is rightfully ranked poorly in comparison to its neighbours.

An alternative and more futures-prepared narrative is that of “all of us are vulnerable” and “all in this together.” This echoes the neo-humanist work of Shrii P.R. Sarkar, who argues that society should be seen like a collective caravan – on a purposeful journey- where no one is left behind. All move forward together. Together. The best example of this is the government of New Zealand where not only did scientific policymaking lead but they also understood narrative and created the story of the nation as a team of six million. In the team, all are important, even if some lead and others lag.

What is now required globally is creating a team of eight billion. In this team, national leaders informed by religious and political dogma need to be constrained by global scientific public policy. All our lives depend on this shift toward science with a new planetary story. New models of global governance are required if we are to make the Age of Pandemics short lived.

REFERENCES

Davey, M. (2020). A peek into the future: how worst-case scenario coronavirus modelling saved Australia from catastrophe. Retrieved from

Inayatullah, Sohail. (2010). Emerging world scenario triggered by the global financial crisis. World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues . Vol 14, No 3:48–69.

Miller, R. (Ed.) (2018). Transforming the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century. Routledge and UNESCO: Paris.

Milojevic, I. (2021). COVID-19 and Pandemic Preparedness: Foresight Narratives and Public Sector Responses. Journal of Futures Studies . Retrieved from https://jfsdigital.org/covid-19-and-pandemic-preparedness-foresight-narratives-and-public-sector-responses/.

Pranavakatmakananda, D. (2017). Shri Shri Anandamurti: Advent of a Mystery. Kolkata: Prabhat Library.

Sarkar, P.R. (1981). The Thoughts of P.R. Sarkar. Kolkata, Ananda Marga Publications.

Yergin, D. (2009). A Crisis in Search of a Narrative. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/8a82d274-bda9-11de-9f6a-00144feab49a.

i Imilojev@gmail.com. Director, Metafuture.org and www.metafutureschool.org

ii sinayatullah@gmail.com. UNESCO Chair in Futures Studies and Professor, Tamkang University.

Imilojev@gmail.com. Director, Metafuture.org and www.metafutureschool.org

sinayatullah@gmail.com. UNESCO Chair in Futures Studies and Professor, Tamkang University.