By Roar Bjonnes

At 66, I am old enough to remember when the local economy was still thriving. I grew up in an extended family on a small island in Norway. All the apples, berries, pears, and cherries we ate, especially during fall and winter, had been cultivated in our own garden. In the fall, the whole family—including my grandmother and grandfather—picked mushrooms, blueberries, and cranberries in the forest. Indeed, all our neighbors lived like that—in a largely self-sufficient and local economy.

A few years later, when I had moved to the US, and I came home to visit, I discovered that the fruit trees and berry bushes had been cut down. The whole garden had been turned into a large lawn, empty of life. “Why had they done that?” I asked. “Well, because it was too much work and these apples from the supermarket are so much shinier,” my sister replied.

I remember that as a very dark and depressing day. I remember it as the day our organic, homegrown apples had become shiny and full of pesticides. I remember it as the day the local economy and culture was destroyed by globalization and its neo-liberal, corporate agenda.

Today, I live in a small eco-village in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina. My neighbors, Kevin and Kate Lane, are organic dairy farmers. They operate Lane in the Woods Farm and Creamery, and they make blue and white cheeses which they sell at several local farmers markets. In a radius of about 100 miles from our doorsteps, there are more than 100 local farmers markets.

I have always prided myself on being an environmentalist. My wife and I grow vegetables and berries for enjoyment and to help lower our carbon footprint. But in these mountains, there are small farmers, deeply conservative, who put me to shame. They do not call themselves environmentalists, but their carbon footprint is much smaller than those of us who shop organic at Whole Foods and vote for the Green Party. We have a lot to learn from these old-timers about sustainability and community values.

Many of these local farmers, as well as the influx of young neo-hippies who have turned hundreds of old tobacco farms into thriving fruit, bee, berry, vegetable, and dairy farms, are members of the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project (ASAP), an organization representing these farmers’ interests. The motto of the organization speaks for itself: “Local Food, Strong Farms, Healthy Communities.”

There are currently more than 12,000 farms in Western North Carolina where I live. In many ways, the local farm economy is thriving, and the farmers markets are bustling economic and cultural ventures where people meet, greet, purchase, and celebrate local food.

When we look at overall economic and environmental trends, however, the global economy is still dominating the local economy. Its centralized machinery, fueled by a fossil energy-driven economy, is still hell-bent on crushing these local efforts. But here in Appalachia, we are fighting back, one small farm, one small farmers market, one local restaurant at a time.

Here in our mountains, the progress of that wholesome struggle for a more thriving local economy speaks for itself. “Twenty years ago,” according to ASAP, “we listed 58 farms, 32 farmers markets, and 19 restaurants in our Local Food Guide. Today, we list over 800 farms, more than a hundred markets, and more than 200 restaurants.”

And, thankfully, in Norway, too, there is a similar trend going on. More and more local products, from smoked meat to various new cheeses, breads, and jams, are sold at local farmers markets all over the country. The growth of the slow food economy is speeding up; it is most certainly experiencing a new renaissance.

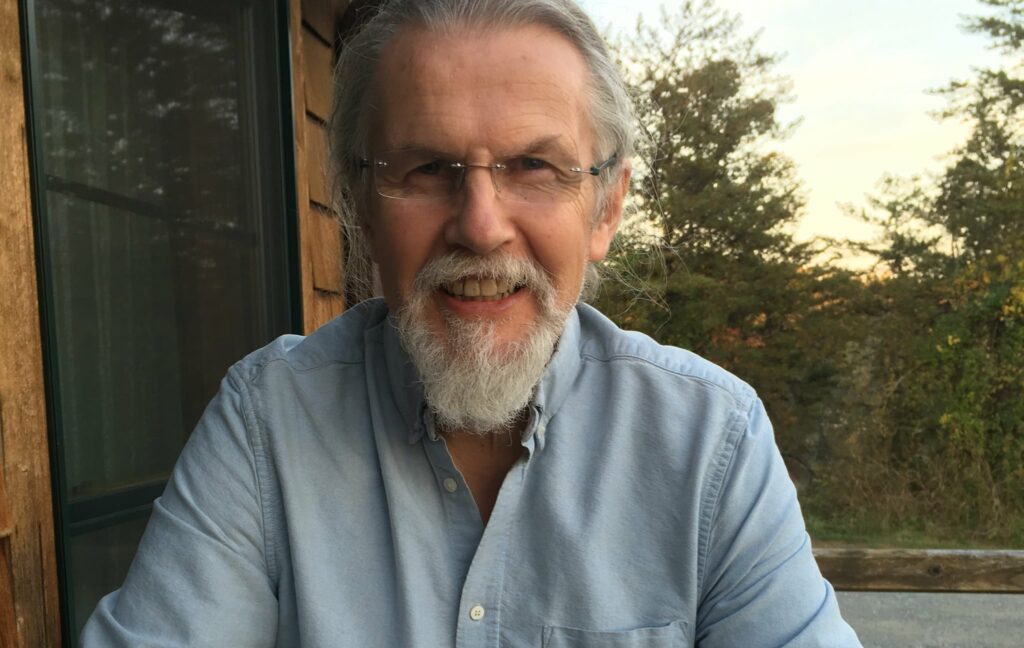

Roar Bjonnes is the co-founder of Systems Change Alliance. He studied agronomy in Norway where he helped organize an agricultural school to become fully organic. He is the author of five books, including Growing a New Economy.

References:

appalachiagrown.org

laneinthewoods.com

slowfood.com